Ethnic weaves: In the tiny village of Chanderi in the Ashoknagar district of Madhya Pradesh, there is little respite from the scorching summer heat as the mercury touches 42 and 43 degrees celcius. There is a preponderance of dry dust on the barren land, which has not seen rain in months.

There is shortage of water, with daily tankers meeting the local people’s meagre needs. The local population, which includes 1,000-odd weavers, could still have coped, but the mortal blow is looming in the form of disappearing demand for their cherished fabric, chanderi.

Yet, in the face of impending doom, there is an air of hope, anticipation and excitement in this sleepy little village, as 455 weaver families are poised to become owners of shares in a community-owned company, a concept totally alien to all except the few educated youths here.

Mohammed Zuber Ansari, 28, has a master’s degree. After failing to find a job, he found himself in front of a loom and is still trying to come to terms with the developments. “We bought shares for Rs 1,000 and all I know is that this could change our lives in some way.”

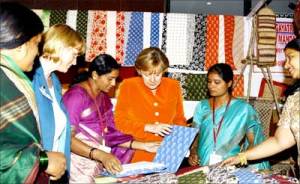

That way has been paved by Fabindia, a retail outfit that has grown from one store in the mid 1990s to 85. Dabbling in fabric, apparel, handicraft and other products, it began an experiment with community-owned companies nine years ago in an attempt to include artisans in the wealth creation process.

Harvard School case study!

The concept, now a Harvard Business School case study, is simple. A fully-owned subsidiary of Fabindia, Artisans Micro Finance, a venture fund, facilitates the setting up of these companies, which are owned 49 per cent by the fund, 26 per cent by the artisans, 15 per cent by private investors and 10 per cent by the employees of the community-owned company.

The investment by these four categories of investors provides the paid-up capital. The company promotes the sales of its artisan community to Fabindia, which is the principal buyer. Eventually the companies will sell to other buyers, too. Haryana and Faridabad have already started independent sales.

After expenditure and tax are deducted from the principal sale value for the year, the year’s profits before and after tax are worked out. Based on this, the valuation of the company and its enhanced share value can be calculated.

The artisans gain in many ways. The value of their shares goes up. They earn dividends when the company is in a position to declare them. Eventually the company will try and offer loans to the artisans, arranged through banks.

Community-owned companies

The loans can be used to buy new looms or expand production of other products. An internal trading mechanism will allow artisans to trade their shares.

Although the villagers see it as a gamble, there is already evidence that it works. A community-owned company promoted a year ago in Jodhpur with a paid-up capital of Rs 34 lakh (Rs 3.4 million) is valued at Rs 1.10 crore (Rs 11 million) . The company, which totted up sales of Rs 5.7 crore (Rs 57 million) and a profit after tax of Rs 22 lakh (Rs 2.2 million) in its first year, has 2,300 artisan shareholders.

Each of their Rs 100 shares is worth about Rs 300. As many of them hold 10 shares each, their investment of Rs 1,000 has tripled to Rs 3,000, an escalation they couldn’t have dreamed of. Through a complicated internal trading system, an artisan can – if he wishes – recover his investment.

Chanderi and Jodhpur are just the beginning. So far 18 community-owned companies have been set up with 6,000 artisan shareholders. Fabindia hopes to set up 100 such companies by dividing its supplier base into clusters. Eventually, the 100 companies will cover 100,000 artisans across 21 states.

Nurturing Hand

Fabindia’s managing director William Bissell, who conceived and steered the model, says that unlike many Indian companies he doesn’t believe in setting up a department to promote corporate social responsibility.

“If one is very serious about CSR, you may have a vice-president heading it. I find a lot of people doing doublespeak. This creates dissonance both within the organisation and outside. This inclusive approach defines our brand and gives it great value. If you do what you believe in, it defines you,” he says.

He is convinced that involving artisans and sharing the benefits of growth with them is the most sustainable of all models. Without that, the market-based system – in his view it is the best system to alleviate poverty – is in danger of being “discredited”.

He quotes Raghuram Rajan’s book to argue that India has moved from phony to crony capitalism and that no one is giving real capitalism a real chance. “If capitalism is inclusive, its chances of getting a bad name go down,” says Bissell. He is giving the final touches to his own book, ReImagining India.

Big plans ahead

The shares offer the artisans a divisible asset class (land can be divided but its divisions are often disputed and jewellery is largely indivisible) and community-owned companies help convert Fabindia’s artisan base into an asset.

“These are not things one can measure on a balance sheet but I do believe that eventually, if we can convert our suppliers or artisans into these community-owned companies, it will be a very strong asset for Fabindia,” says Bissell.

But the model is not desirable from a social point of view alone. Fabindia has moved from being a primarily export house in the 1960s to a turnover of Rs 300 crore (Rs 3 billion), of which 90 per cent is domestic sales. Its aim is to be a “lifestyle alternative to the mass-produced”.

From soap and organic food to clothes and furniture, it claims to provide ‘natural and eco-friendly’ options. These options are sourced primarily from craft-based processes. While the company doesn’t set targets, it is looking at growing to 250 stores in four years.

Element of the hand

Artisans Micro Finance director Smita Mankad quit ABN Amro to do something she believed was worthwhile. “If you want to grow at the pace we have grown, you have to carry your supplier base with you,” she says, emphasising that Fabindia’s growth will be hampered unless the artisans grew with it.

Everything Fabindia sells has the “element of the hand” in it, so one can’t step up production overnight like in China’s mass-produced factories. The community-owned companies offer the persons owning the hands a better life, such as, by providing an alternative to the local Shylock.

“If he wants to get his daughter married and needs money, he can sell his shares and realise the appreciation. He can also take a loan by offering his shares as collateral,” says Bissell.

Making a big difference

Fabindia is changing the way the artisans work, the new model is changing the way Fabindia works. The typical central warehouse system has given way to several warehouses owned by community-owned companies from which goods travel directly to stores across India. This reduces logistics costs and minimises the role of middlemen.

While the system seems to be working for all concerned, challenges remain. One of them is developing secondary markets so that the companies can stand on their own feet.

Critical to that will be introducing a “consciousness” of the design element in the artisans so that their products have a wider appeal. Bissell says the model will depend on the artisans beginning to understand the benefits of joining together in something that’s not a cooperative.

“A cooperative imposes many restrictions upon them and doesn’t give them much in return. If you get together, you must create something that’s bigger than the sum of the parts.”

That seems to be happening in Chanderi. Ansari says his family of seven had tired of poverty and an uncertain future. Weavers were down to earning Rs 13 a meter and haggling with the “seths” on a per saree basis. Payments were erratic. His fellow weavers had begun to leave the village in search of alternative livelihoods.

A Unido project tried to help, but FabIndia’s entry made the biggest difference as it began to source fabric worth Rs 1 crore (Rs 10 million) a year from Chanderi. The realisation has risen to Rs 23 a metre. Ansari’s two looms are busy all day. Safely tucked away are 10 shares and the promise of a better future.

Courtesy:- Rediff

No comments:

Post a Comment